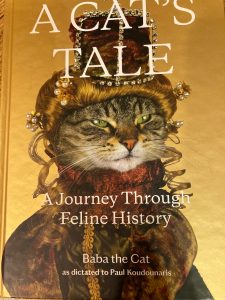

I’ve been reading Paul Koudounaris’s (and his cat, Baba’s) book, A Cat’s Tale, a Journey Through Feline History. Very interesting—a beautiful book full of a fascinating history of the cat as told by Baba, who has an incredible mastery of the language. All joking aside, it’s obvious and documented, that Baba’s owner/coauthor did an enormous amount of research. He did say that, during the research and writing process, Baba sat with him a lot and stared at the manuscripts. One day, Paul turned a page upside-down and Baba actually pawed at it until he righted it. Interesting tidbit!

I’ve been reading Paul Koudounaris’s (and his cat, Baba’s) book, A Cat’s Tale, a Journey Through Feline History. Very interesting—a beautiful book full of a fascinating history of the cat as told by Baba, who has an incredible mastery of the language. All joking aside, it’s obvious and documented, that Baba’s owner/coauthor did an enormous amount of research. He did say that, during the research and writing process, Baba sat with him a lot and stared at the manuscripts. One day, Paul turned a page upside-down and Baba actually pawed at it until he righted it. Interesting tidbit!

Among the feline history they share, they write about  the first real working cats to make a salary and to make history as working cats. Now, I’ve written about working cats—those cats that grace small and large businesses throughout the world—sentries at the threshold of important buildings, greeters at museums and other such institutions, classroom cats, library cats, bookstore and pet store cats, cats that work in nurseries and so many more. Cats were used aboard ships, they were enlisted into the armed forces and Baba tells stories in her book about some of the earliest jobs of the first cats in America. For example, ever hear of postal cats?

the first real working cats to make a salary and to make history as working cats. Now, I’ve written about working cats—those cats that grace small and large businesses throughout the world—sentries at the threshold of important buildings, greeters at museums and other such institutions, classroom cats, library cats, bookstore and pet store cats, cats that work in nurseries and so many more. Cats were used aboard ships, they were enlisted into the armed forces and Baba tells stories in her book about some of the earliest jobs of the first cats in America. For example, ever hear of postal cats?

At one point, thousand dollars a year was appropriated for food for postal cats throughout the US. They protected the mail, of course, from rodent damage. Cats also worked in military storehouses. Each of these cats got $18.25/year toward their keep.

At one point, thousand dollars a year was appropriated for food for postal cats throughout the US. They protected the mail, of course, from rodent damage. Cats also worked in military storehouses. Each of these cats got $18.25/year toward their keep.

According to Baba, people knew that cats had greater value than as mousers and they began to think of other “jobs” cats could do. Deep-thinking professors got in on the contemplation—one suggesting that cats could be used to protect property from lightning strikes. One brilliant thinker evidently considered using cats to protect people caught in burning buildings (I have to wonder if Baba was on something when he dictated this book). How, you ask? This is beyond my comprehension, but here it is—cats would gather below the burning building to cushion the fall of people escaping the blaze.

wonder if Baba was on something when he dictated this book). How, you ask? This is beyond my comprehension, but here it is—cats would gather below the burning building to cushion the fall of people escaping the blaze.

There were even those who wanted to teach cats to sing—using their variety of mews and yowls to create music.

There were even those who wanted to teach cats to sing—using their variety of mews and yowls to create music.

Baba wrote that during the migration by covered wagon to the west, cats were often taken along to protect the food they carried and the pioneers had to pay as much as $10 per cat as cats were scarce at the time.

Once everyone was pretty much settled in the towns that were springing up, people began following their passion in art and writing and needlework. Artists and writers took a new interest in cats and used them in their writings and their art and as their inspiration. Cats had found a warmer, more cozy place in America, having earned it, wouldn’t you say?